What exactly defines a failure of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)? We obviously can’t blame it for every single recall of a contaminated food item or dangerous drug – it isn’t omniscient. We can, however, look at the circumstances, knowledge, and actions of the Administration case-by-case and find some disturbing trends.

The truth is that FDA failures are fairly common. One recent example you’ve probably heard about is the mass of baby food recalls – where the FDA had prior notification of heavy metals and contaminants in numerous baby food products and failed to act in a timely manner, allowing thousands of infants to continue to eat contaminated food.

And though it’s not necessarily fair to think failures like these are “all the FDA’s fault,” it certainly must shoulder some blame. The Administration is empowered to enforce food safety standards, conduct food safety inspections, and analyze and approve any new drug or medical device. But there are also many bureaucratic and political difficulties involved.

So, while it would be easy to approach this subject with animosity toward the FDA, I want to do a bit of digging. I want to understand. This article explores regulatory mistakes and why they happen, and asks the question:

What are the fundamental failures of the FDA, what risks do these failures pose to you and me, and how do they affect our everyday lives?

Failure #1: User Fees, Pharmaceutical Companies, and Drugs We Probably Don’t Need

In 1992, Congress passed the Prescription Drug User Fee Act (PDUFA). Boiled down to the basics, the law enables the FDA to collect large “user fees” from pharmaceutical companies or device manufacturers seeking approval for a new drug or medical device. The catch is that the ability to collect those fees depends in part on the FDA’s speed in completing the new drug approval process.

The language of the law is relatively vague on the “speed” front, but the fees helped increase staffing and reportedly cut drug approval times by half. The fees are not insignificant – the expected fee intake to the FDA was nearly $300 million in 2007. In 2023, it’s expected to be $3 billion.

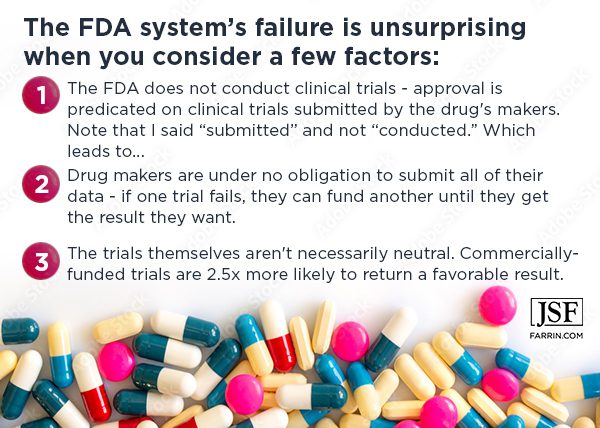

This creates a somewhat obvious conflict of interest that, according to research, has resulted in prevalent institutional corruption. Pharmaceutical companies are paying big money to get new drugs through the approval process. The result is more new drugs, faster. But are they really better? Is the FDA allowing itself enough time to conduct a thorough analysis of these drugs?

Most importantly, are these new drugs safe?

New Drugs Are Mostly No Better Than the Old Ones

According to research, few new drugs are significantly better than what we already had. Decades of independent reviews found that just 11-15% of new drugs have significant clinical advantages over their predecessors. Research from Canada, France, and the Netherlands between 2002 and 2011 found that, of 946 new products, only 13 represented a therapeutic advance, eight were clinically superior, and only two were breakthroughs.

A congressional/legal mandate to get drugs approved faster has translated to fewer trials performed. That’s why, in addition to not being improvements, new drugs are harming many people.

After the 1992 law was passed, drug approval times went down by half. However, just a 10 month reduction in review and research time can result in approximately:

- 18% more adverse reactions

- 11% more hospitalizations

- and 7.2% more deaths from new drugs

Failure #2: Underfunded and Lax Regulatory Oversight in the Face of Record Pharma Profits

Even though very few new drugs offer breakthrough results, the drug business is doing quite well. Pharmaceutical companies’ return on revenue (ROR) is more than 3x that of other Fortune 500 companies.

Meanwhile, an already compromised FDA has impossible inspection tasks to perform. As of 2023, there are 2,655 brand-name pharmaceutical manufacturers in the U.S. alone. Each of these facilities is supposed to be inspected regularly by FDA officials. That’s just not happening – and isn’t necessarily helping even when it does. And the FDA is also supposed to inspect manufacturers outside of the U.S. if their products will be sold here.

A Kaiser Health News investigation from 2013-2019 revealed that 65 drug-making facilities recalled nearly 300 products within 12 months of the facility passing an FDA inspection.

Examples included:

- 39,000 bottles of HIV drug Atripla laced with red silicone rubber particulates

- 37,000 Abilify mood disorder tablets that were mistakenly “superpotent”

- 12,000 boxes of generic Aleve (naproxen) that were actually ibuprofen

- Over-the-counter ducosate sodium, an anti-constipation drug, contaminated with deadly bacteria

The last of those examples was from a plant in Florida that passed its FDA inspection even as it was producing the contaminated drug.

Inspectors Are Working With Complicated Language and Antiquated Tools

At the time of the above-mentioned bacterial contamination of constipation medication, Food and Drug Administration Commissioner Scott Gottlieb said that the FDA drug oversight program was the “gold standard.” An industry consultant who trains inspectors had the opposite opinion, and described passing inspections as “too easy.” He cited confusing regulatory terminology, outdated standards, and antiquated tools as reasons FDA inspectors missed things.

The FDA Doesn’t Always Listen to Its Own Advisors

In 2018, Dr. Raeford Brown, the chair of the FDA’s opioid advisory committee, unleashed a scathing rebuke of agency officials. He claimed that there was a war within the Administration, echoing in some ways the physician who first perceived the opioid crisis, Andrew Kolodny. Dr. Brown was staunchly opposed to the FDA’s approval of Dsuvia, a more powerful version of fentanyl, and a drug even four U.S. Senators urged the Administration not to approve. The FDA approved it anyway.

The FDA Often Fails to Demand Sufficient Clinical Evidence of Claims

While the FDA does not necessarily control every word on the packaging of a drug, it certainly has the power to stop improper pharmaceutical marketing. Purdue Pharma, makers of OxyContin, one of the primary players in the national opioid epidemic, used one particular sentence on its label that was not supported by evidence and may have helped ruin many lives:

“Delayed absorption, as provided by OxyContin tablets, is believed to reduce the abuse liability of a drug.” Except that no clinical studies established any reduced likelihood of addiction. Furthermore, Purdue claimed that the “delayed absorption” language was added by the FDA, which must approve all label language prior to launch.

The sentence remained on the label for more than five years before the FDA replaced it with a sobering “black box warning.” Purdue pushed the drug and its “lower risk” of addiction to the tune of more than $35 billion since 1996 when it was first marketed. The opioid crisis has resulted in enormous settlements with multiple states from makers and distributors of the drugs, but the FDA’s testing, approval, and recall failures deserve much blame, too.

For all the reasons above and more, there are many new drugs and treatments that may be barely tested, hastily approved, questionably marketed, and sometimes deeply flawed and dangerous.

Failure #3: Food Regulation Takes a Back Seat to Everything

Apart from meats, milk, and eggs, which are regulated by the USDA, the FDA oversees the American food supply. In 2011, the Food Safety Modernization Act overhauled food production regulations and gave the FDA the authority to oversee the supply chain. In theory, it could shift the focus from reacting to food-borne illnesses to preventing them.

In practice, food safety efforts are reportedly no better today than they were in 2011. In fact, the agency’s funding, focus, and bandwidth are largely on the drug side according to a former acting commissioner. The “food” part of the Food and Drug Administration lags far, far behind.

Food Safety Efforts Are Often Just Delayed Reactions

A POLITICO exposé on the subject uncovered dozens of people willing to candidly criticize the food side of the administration, from inside and out. That story laid bare the grim state of affairs at the FDA and provoked a direct public inquiry from a member of the Senate Health Committee.

Food safety efforts appear to often be token at best and broken at worst. The FDA is slow to respond to food crises and seems to do little as far as prevention is concerned. The results can be catastrophic, victimizing the most vulnerable among us.

Example of Food Safety Failures by the FDA: Infant Formula & Baby Food

Infant Formula

If food supply safety is important to anyone, it’s infants. Infant formula, it reasons, would be a focus of safety efforts. The first reports of infant illness related to contaminated formula from Abbot Nutrition hit the FDA in September 2021. Inspectors were dispatched to the Sturgis, MI production facility in January 2022.

The product recall didn’t come until February, five months later.

Baby Food

Foodborne illness is bad, but what if the problem is not a pathogen but a toxin? Reported in 2017, an independent lab found heavy metals, lead, and arsenic in the baby food they studied. The FDA’s response was quick – but dismissive. When the lab showed that their testing was in line with the methods the FDA used, it got no further response from the Administration.

In 2021, a report was released detailing how many baby foods contained levels of toxic elements far beyond the generous limits set by the FDA. A recall ensued – four years after the problem was brought to the Administration’s attention.

I’m not even touching on the many, many instances of contaminated food – especially produce – that grace the news with alarming regularity. There are many examples of foodborne illnesses and pathogens wreaking abrupt havoc, sickening many people, and sometimes resulting in deaths. The FDA’s response is often quite tardy – if it responds at all.

Failure by Design – Underfunding

People are right to be angry about the sad state of the FDA’s food safety efforts and the real and looming threat to our food supply. And while the failures lie at the feet of the FDA, that’s not necessarily where the buck stops. In fact, the problem may be that not enough bucks have stopped at the FDA. The administration isn’t getting properly funded – and hasn’t for years.

The passage of the Food Safety Modernization Act in 2011 was supposed to be a turning point, but the funding didn’t follow, according to reports. In the four years after the passing of the law, the FDA hadn’t even received half of the necessary money. While the 2023 budget is $8.4 billion, more than a third of it is user fees. The food budget is reportedly $1 billion – less than 15% of the overall budget.

Failure #4: Organizational Gridlock and Byzantine Structure

Where in the government is the FDA exactly? In the sense of organizational pecking order, the FDA is housed under the Department of Health and Human Services. And it is in disarray.

There’s too much competition and confusion in the FDA for it to fully focus on the regulatory affairs with which it is charged. It is apparently lethargic at the best of times. And the FDA is historically unwilling to put a deadline on anything. Even when it does, it generally blows months or years past it.

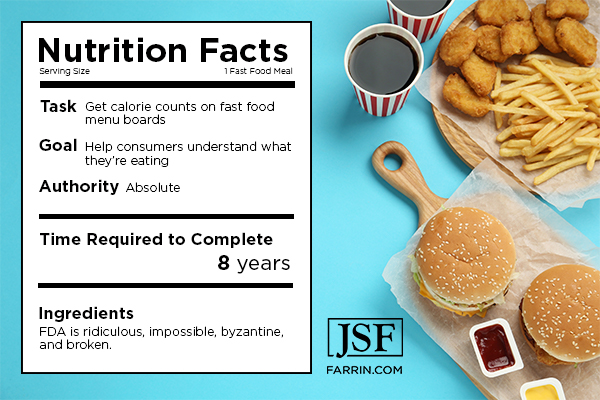

For example, it took nearly eight years to get changes to nutrition labels and calorie counts on fast food menu boards. The words that were used to describe the FDA included ridiculous, impossible, byzantine, and broken.

Change Is Necessary at the FDA

The FDA’s oversight of food policy, drug safety, and general public health just isn’t working well enough, though as I’ve noted at a couple of points, the FDA’s failures are not entirely its fault. The result of nearly a hundred years of Congressional tinkering, government meddling, terrible communication, added responsibilities, inadequate staffing, mixed signals, and plain confusion is a dysfunctional FDA.

As a lawyer whose job is to challenge industries on behalf of people injured by their products, I’m deeply concerned and incredibly frustrated to know that more prevention is possible. FDA failures have contributed to many broken lives. Many of the illnesses, injuries, and deaths of American consumers by faulty food products and bad drugs could be prevented with better regulatory attention, stricter standards, and clearer policy.

Don’t Depend on the FDA, and Don’t Let Companies Get Away With Harm

When you’re hurt by a bad drug or contaminated food, the FDA’s failures hit close to home. You’re sick. You’re injured. And you should not suffer the burden of treatment and recovery when your injury or sickness is the result of someone else’s negligence, especially when that negligence should have been better prevented by the taxpayer-funded FDA.

And though people have sued the FDA and won in the past, ultimately, the duty of care belongs to the makers and distributors of the foods and drugs we consume. And that’s who you can fight back against when the FDA lets you down.

We Help Hold Companies and the Government Accountable

Have you been harmed by a defective drug or contaminated food product? We can help protect your rights and try to hold manufacturers accountable for their negligence.

You may have heard of Camp Lejeune, another situation where lax government oversight led directly to the harm of many. We’re currently helping many of those affected by the contaminated water at Camp Lejeune fight for government accountability.

We’ve helped more than 73,000 people recover more than $2 billion in total compensation since 1997.1 We work for and with our clients, and in your best interests – we put you first.

Even if the FDA doesn’t.

For a free case evaluation, call 1-866-900-7078 or contact us online today.